What "Parse, don't validate" means in Python?

Stuff you knew without knowing you knew

Summary

"Parse don't validate" is common wisdom, but it’s quite confusing. In real life, we both validate and parse, often very close to each other, sometimes several times in a row.

In fact, parsing implies coercing to a proper type, and failing to do so is validation in itself, so parsing is really validation, only with understanding.

But what does that mean for Python?

Since it’s a higher-level language, you will rarely analyze bytes yourself, so it will mostly be about turning a data structure into another, more structured one.

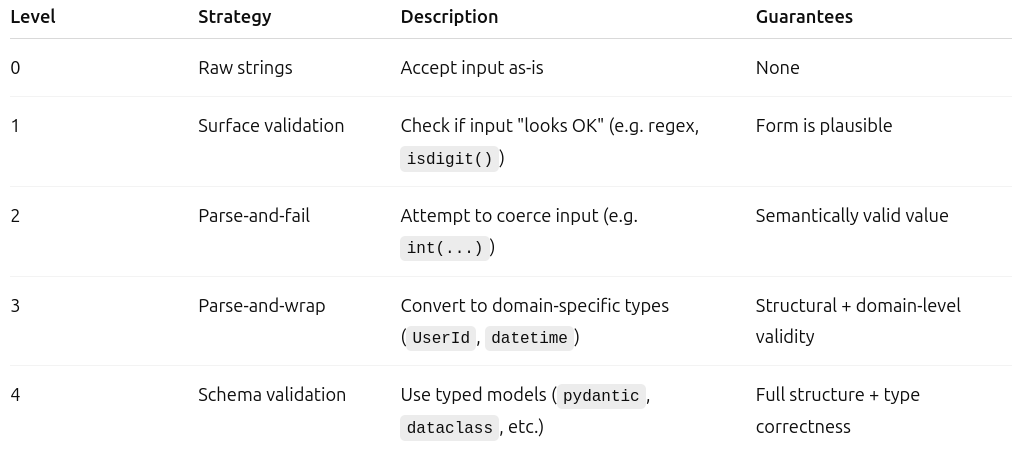

You will have to focus particularly on how much you want to parse and decide where to put the cursor on the effort/reward spectrum. The more meaning you extract, the more sophisticated the type you create, the more trust you add to the boundaries of your code. But also, the more work you have to invest upfront.

Duh

Like KISS or DIY, "Parse, don't validate" is an old idea you may hear greybeards repeating in one form or another, without you necessarily getting what it means in practice.

As it's often the case in programming, bad tutorials, unnecessary jargon, and the desire to look much more intelligent than we are, may have obscured a little bit what is, at its core, a simple concept:

When you get input, extract meaning from it to turn it into a proper type.

Yeah, that looks less like profound wisdom when you state it like that.

In fact, if you ask a user "what is your age?" in a text box, "Parse don't validate" in Python can mean something as basic as:

try:

user_age = int(user_age)

except (TypeError, ValueError):

sys.exit("Nope")Validating would be:

if not user_age.isdigit():

sys.exit("Nope")Ok, so why do people keep repeating that?

Let's define a few things

By "input", I mean your program input, not any function input. So this concerns code that is at the boundary between the external world and the internal state: stuff that analyzes command line arguments, HTML forms processing, search query results, reading a JSON file, etc.

E.G:

# That's program input since the data comes from outside of your code

for row in cursor.execute("SELECT id, name FROM users"):

print(row)By "validate", I mean make sure the input data is sufficiently close to what you think you can use without errors. Does the age look like a positive integer number? Is this line of CSV file what you think it is? Can you make sense of it later in the program?

E.G:

# That's validation: we check our expectation

if age < 0:

raise BenjaminButtonError("Yeah, no") By "parsing", I mean taking low-level data or unstructured data and turning it into higher-level data or more structured data. Finding a few bytes in a PNG and turning them into RGB pixel color values is parsing, but so is reading an already decoded text file containing TOML and turning it into nested dictionaries, lists, and scalars.

E.G:

# That's parsing, we separate two chunks of data that used to be

# merged into clean and obvious buckets

from email.utils import parseaddr

name, addr = parseaddr("Bite Code <contact@bitecode.dev>")

print(name) # "Bite Code"

print(addr) # "contact@bitecode.dev"Input, parsing, and validation are layered again and again, because we have so many abstractions nowadays, and Python does a lot of things already. It validates a lot, and it parses a lot for you, before your code even gets the chance to run.

You don’t have one input, one parsing, one validation: they happen several times. Depending on where you are, some of it concerns you, or not.

E.G, getting your program input from the command line in Python is:

import sys

print(sys.argv)But a lot happened before that. C itself got an input of bytes, and it took that and validated it, checking it was valid text. Then parsed it to convert it to a `str` type, then parsed it again to make it a `list[str]` type, then stored it into `sys.argv`.

So your input comes after this whole dance of input/validation/parsing.

And on this input, you can add your own validation and parsing:

import argparse

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(description="Spline reticulator")

parser.add_argument("file_path")

parser.add_argument("--verbose", action="store_true")

args = parser.parse_args()So, in reality, "Parse don't validate" is quite confusing. In real life we both validate AND parse, often very close to each other, sometimes several times in a row. One could even choose to define parsing as extraction + validation, followed by choosing the right type to represent the result.

In that sense, parsing is validation, but with understanding.

When is it enough parsing?

In a world of dynamic languages and millions of libraries, the chances of you dealing with raw bytes are rare, so in Python, this means you will often turn a high-level type into an even higher one. In fact, bytes is already quite high-level itself!

You may now wonder, then, why parse? We are already in a high-level language, I have high-level types, isn't it overdoing it?

And as usual, it depends on what you gain out of it for the price of it.

Parsing is a way to state that "now that I've processed that data, all code that follows after this can benefit from":

The pre-calculation you may have done. If you convert

bytestoutf8, or JSON to dodict+list+str+float, no need to do it twice.The convenience of the structure you get. If you have a

contact.csvwith lines like"name;last name;address;phone", a tuple("name", "last name", "address", "phone")is easier to manipulate than the raw text for the functions that come after.The certitude it's safe to proceed. If you have turned a user form into a

User(name='BiteCode', age=99) dataclass, it's safe to assume in the rest of the code that this user has all the fields it needs.

So, parsing communicates with the rest of the code, and even establishes a contract with the rest of the code, telling it it can relax its own requirements because some work is done, and we agree on what the result is.

It also includes some validation since coercion to the proper type fails if the data is bad.

Because of all that, parsing transforms not just types but trust boundaries, and the more you do it, the more you get trust.

Ok, but concretely?

Some of those statements seem evident, and in fact, you may have wondered what's so special about it.

Of course, if I parse JSON I'm not going to parse it again every time I need the data!

In this very obvious case, you would do:

config = json.loads(open(path))

def setup_log(config):

...

def intialize_db(config):

...But not:

def setup_log():

config = json.loads(open(path))

...

def intialize_db():

config = json.loads(open(path))

...The second one would work perfectly, yet even if we probably all did it while learning programming, it now feels instinctively wrong.

However, what about a URL?

Do you pass it around as text?

def ddos(url):

bypass_cloudflare(url)

click_on_the_traffic_lights(url)

really_slam_the_server(url)

def ask_for_ransom(url):

email = find_abuse_contact(url)

ask_for_bitcoins(email)

URL = "https://bitecode.dev"

ddos(URL)

ask_for_randsom(URL)Or do you call urllib.parse.urlparse() and pass around an instance of urllib.parse.ParseResult?

from urllib.parse import urlparse

def ddos(url):

bypass_cloudflare(url)

click_on_the_traffic_lights(url)

really_slam_the_server(url)

def ask_for_ransom(url):

email = find_abuse_contact(url)

ask_for_bitcoins(email)

URL = urlparse("https://bitecode.dev") # parsing!

ddos(URL)

ask_for_randsom(URL)The difference... seems to be not that much!

And if you parse, do you parse it into something simple or rich? Like, for a user form, do you make it a tuple ("BiteCode", 99), a dict {"name": "BiteCode", "age": 99} or a dataclass User(name='BiteCode', age=99)?

All those options are valid. In Python, we rarely have to choose between "Parse" or not "Parse", we have to think more about how much to structure it.

So, how do you decide?

In the URL example, you have to ask yourself, do those calls:

bypass_cloudflare(url)

click_on_the_traffic_lights(url)

really_slam_the_server(url)

...

find_abuse_contact(url)really need a full URL or some parts extracted from it? Do you want validation for free since they come with the parsing? Can you edit those functions or do you have to pass a type that they expect?

This is what will determine if you parse a lot or not.

In some other instances, it's a matter of performance. E.G: I love pathlib and it's much nicer to manipulate a Path than to pass a str to os.path functions. But pathlib is slow. Does that matter for this program?

Probably not, I'm already choosing Python, because the productivity I gain from it trumps the speed, but it's not an absolute rule. Sometimes it does.

All in all, it's a matter of how much you want to invest in this code. A quick script warrants much less parsing than a lib you are going to share with thousands of people.

Just like a contract for a small deal must be less air-tight than a multi-billion-dollar one.

Failing early, and failing at failing

One of the most important consequences of the “Parse, don’t validate” principle is that it forces you to fail early. When you only validate, you can still debate whether you should put a return or a raise right there or not.

But when you parse, either stuff makes sense and you can carry on, or they don’t, and there is not much you can do.

This has the interesting side effects of making edge cases, such as empty containers or infinite streams, more apparent as well.

I’m not saying you can’t do that with validation, of course, I’m saying that it’s more in your face.

Now, Python has nullable types (since it has None) with few facilities to nicely deal with them. No monad, no Option, no Result, no maybe. It also has an exception-based error system that cannot be encoded with type annotations. So we are pretty far away from what you can achieve with languages that have great support for such situations. This is why in the famous Alexis King’s article that coined the adage, there is a focus on things that won’t ring a bell in Python: we simply don’t have the right tooling to get so many benefits.

We are stuck with if is not None, dict.get, try/except you clawed out of the documentation (or pain) and in the best case but rare scenario, match/case. And Python, being forgivingly dynamic, trusts you with its life and will not complain if you forget that this list can contain zilch, that this fetch can return None, and that this concurrent call can explode in your face with a colorful ForkYouError.

In that sense, “Parse, don’t validate” brings less to the snake’s table than in Ocaml, Haskell, or even Rust or C#.

That’s the nature of the compromise you get with Python: trading flexibility for guarantees.

But for other things, Python has your back

One more article where I conclude that "it depends". One day, you are all going to unsubscribe using ChatGPT German translated insults, but I swear I mean well.

But yeah, you should parse and validate; however, how much you do that is an exercise left to the coder.

Luckily, Python is well-equipped to give you a wide range of choices:

It comes with a lot of different levels of abstractions, so you can choose to use simple types, complex ones, or a mix of them, nested into rich data structures. But do choose.

It has dynamic typing with optional annotations. So you can write quick code and pass around barely parsed stuff because you don't care, or you can carefully craft your API so that each type is a precious jewel that informs the readers, protects the callers, and makes the maintainers smile.

It provides many libraries that will do a lot of parsing for you in the stdlib, and a ton more in Pypi.

You can pass around a date as a well-parsed datetime.date(2001, 1, 1) or, as minimally parsed "2001-01-01", you can annotate a function to accept date, date: str, date: datetime.date or date: str|datetime.date. You can ask arrow to parse stuff for you and let it deal with it.

I will leave you with 3 tips.

Tip 1, you can still use scalars.

Thanks to typing.NewType, a type can just be a marker saying "this is what you want".

Let's say you have a User Id you get from a URL. Just validating would be this:

url = "https://example.com/user/U6789679"

uid = extract_user_id(url)

validate_user_id(uid)And you could argue `extract_user_id`is’s a tiny bit of parsing, but we lack a good type at the end. It’s still all strings.

Full parsing could be this:

@dataclass

class UserId:

value: str

@classmethod

def from_url(cls, url):

uid = extract_user_id(url)

validate_user_id(uid)

return cls(value=uid)

uid = UserId.from_url("https://example.com/user/U6789679")But that seems a bit overkill, doesn't it? A whole class for just a User Id.

What you want is the rest of your program to know that it's been extracted and validated, and it can trust it's correct.

We have a middle ground for this nowadays:

from typing import NewType

# Declare a new type of string that is marking stuff

# as a valid user id

UserId = NewType('UserId', str)

# in Python 3.12, you can replace the 2 lines above with

# type UserId = str

def parse_id(url: str) -> UserId:

uid = extract_user_id(url)

validate_user_id(uid)

return UserId(uid)

uid = parse_id("https://example.com/user/U6789679")UserId, here, is still a regular string; you get no overhead, it will work everywhere strings work. Now you can tell the entire world that some strings are a valid - cross-my-heart - User Id, by marking them.

And the rest of the world can say that's what they want:

def load_user(user_id: UserId):

...

load_user(parse_id(url)) # yep!

load_user("U6789679") # nope!This won't trigger an error in Python, though. You have to use a type checker like mypy, pyright, or ty to get the warning. But it's a lightweight alternative, and even without tooling, it tells other programmers what parts of the program do what.

The second tip is that even built-in containers can be typed. Let’s say you parse some user data from this JSON:

[

{

"username": "SCP-173",

"age": "29",

"last_login_date": "2025-07-21T14:30:00"

},

{

"username": "rogersimon",

"age": "34",

"last_login_date": "2025-07-20T09:15:00"

},

{

"username": "admin",

"age": "22",

"last_login_date": "2025-07-18T23:45:00"

}

...

]Sure you can go full dataclasses for those (and it can be nice), but you don't have to. You can just use regular dicts and mark them with typing.TypedDict

import json

from datetime import datetime

class User(TypedDict):

username: str

age: int

last_login_date: datetime

raw_data = json.load(open("users.json"))

# Now users is marked as containing a list of dictionaries, but

# with each with a very specific structure

users: list[User] = [{

"username": entry["username"],

"age": int(entry["age"]),

"last_login_date": datetime.fromisoformat(entry["last_login_date"])

} for entry in raw_data]

The syntax is verbose (I wish we had something like in TypeScript for them), but you don't pass a class around, you stay with a simple dictionary, albeit with proper str, int, and datetime objects, with a nice type declaration.

And of course, you can decide not to mark them at all, that's why type declaration is optional in Python after all: to give you the option. Python is still Python. You don’t have to make things complicated. But if you need to, you can.

The third tip is, if you need full throttle parsing and validation, Pydantic is your best friend.

The code above becomes:

from datetime import datetime

from pydantic import BaseModel, TypeAdapter

class User(BaseModel):

username: str

age: int

last_login_date: datetime

raw_data = open("users.json").read()

users = TypeAdapter(list[User]).validate_json(raw_data)And now you have a list of perfectly parsed and validated User objects.

That's a lot of parsing in a few lines if you count:

Python parses bytes, turns them into text.

TypeAdapterparses JSON, turns it into Python built-ins.The

Usermodel parses that and turns it into a class instance.

So you will parse no matter what. But now you know how much extraction, validation, and type declaration you need is the important metric to ponder.

Keep in mind the core motivation is to fail early and extract structure, not just to be more Pythonic. This will help with security and fault-tolerance concerns, albeit to a lesser degree than when dealing with binary formats in C or parser combinators in Haskell.

Thank you for the article. There are in fact discussions and proposals to model exceptions in the type annotations. It did not go far AFAIK but it's a recurring discussion.

Funny typo: Ocalm instead of Ocaml, specially for a French speaker.

One of the influential sources of the "parse, don't validate" mantra is https://lexi-lambda.github.io/blog/2019/11/05/parse-don-t-validate/