Pydantic can do what?

Course I knew it, just making sure you knew it

Summary

Pydantic has grown so Fast, and it now contains a full-featured settings loader system with support for getting values from env vars, multiple dotenv files, config file, and cloud vaults.

In fact, it can even parse CLI arguments now.

Today, you can effectively replace calls to environs/dotenv, click/typer/argparse, tomlib/yaml/json, and most parsing+validation code with a Pydantic class.

And it will cascade all those, deal with missing sources, handle priorities, understand deeply nested values, and censor secrets.

It’s quite good, I would say.

Pydantic is a chonky boï now

Pydantic started as a simple validation library, like marshmallow, and is mostly used as such today. You first define a schema:

>>> from pydantic import BaseModel, HttpUrl, ValidationError

... from datetime import date

...

... class Book(BaseModel):

... title: str

... url: HttpUrl

...

... class LibraryCheckoutRequest(BaseModel):

... date: date

... user_id: str

... books: list[Book]Then you validate data with that schema. If it works, you get a regular object you can manipulate that you know contains exactly what you want:

... valid_request = LibraryCheckoutRequest(

... date=”2025-11-21”,

... user_id=”user123”,

... books=[

... {”title”: “1984”, “url”: “https://library.example.com/books/1984”},

... {”title”: “Brave New World”, “url”: “https://library.example.com/books/brave-new-world”}

... ]

... )

...

>>> valid_request

LibraryCheckoutRequest(

date=datetime.date(2025, 11, 21),

user_id=’user123’,

books=[

Book(title=’1984’, url=HttpUrl(’https://library.example.com/books/1984’)),

Book(title=’Brave New World’, url=HttpUrl(’https://library.example.com/books/brave-new-world’))

]

)

>>> valid_request.books[0].url.path

‘/books/1984’And if the data is invalid, it will tell you so, and what the problem is with it:

... try:

... invalid_request = LibraryCheckoutRequest(

... date=”not-a-date”,

... user_id=123,

... books=[

... {”title”: “Invalid Book”, “url”: “not-a-url”}

... ]

... )

... except ValidationError as e:

... print(e)

...

3 validation errors for LibraryCheckoutRequest

date

Input should be a valid date or datetime, invalid character in year [type=date_from_datetime_parsing, input_value=’not-a-date’, input_type=str]

For further information visit https://errors.pydantic.dev/2.12/v/date_from_datetime_parsing

user_id

Input should be a valid string [type=string_type, input_value=123, input_type=int]

For further information visit https://errors.pydantic.dev/2.12/v/string_type

books.0.url

Input should be a valid URL, relative URL without a base [type=url_parsing, input_value=’not-a-url’, input_type=str]

For further information visit https://errors.pydantic.dev/2.12/v/url_parsing

It can also serialize/deserialize data to JSON and is compatible with type hints, for this reason, it was eventually adopted by FastAPI to define endpoints in an succinct and elegant way, and became very popular.

So they added more stuff.

What do you mean, it does settings?

Over time, Pydantic has accumulated more and more features, and one day made an innocent addition: a small class dedicated to loading values from environment variables and validating them. It has since grown, and grown, and it’s now an unexpectedly excellent settings loader system.

It has become so much more than it was at the beginning, in fact, that in 2023, the code was extracted into its own separate package: pydantic-settings.

Here is a simple example:

# /// script

# dependencies = [

# “pydantic_settings”

# ]

# ///

from pathlib import Path

from typing import Literal

from pydantic import SecretStr, Field, DirectoryPath, conint, HttpUrl, ConfigDict

from pydantic_settings import BaseSettings

class Settings(BaseSettings):

service_url: HttpUrl

api_token: SecretStr

log_level: Literal[’DEBUG’, ‘INFO’, ‘WARNING’, ‘ERROR’, ‘CRITICAL’] = ‘INFO’

upload_dir: DirectoryPath = Path(”/tmp/uploads”)

port: conint(ge=1024, le=65535) = 8080

model_config = ConfigDict(

env_file=(”/etc/.env”, “.env”),

env_file_encoding=”utf-8”

)

if __name__ == “__main__”:

settings = Settings(log_level=”WARNING”)

print(”Service URL:”, settings.service_url)

print(”API Token:”, settings.api_token)

print(”Log Level:”, settings.log_level)

print(”Upload Directory:”, settings.upload_dir)

print(”Port:”, settings.port)

In a few lines, you already get so many things:

This will load all values from a

/etc/.envthen a.envfile if they exist.This will then load all values from environment variables. They override the previous values.

This will then override those with any parameters manually passed to

Settings.Then it will deserialize all those values into proper Python types.

upload_dirwill be aPath, for example.And finally, it will perform validation. Check if the port matches the given range. That the log level is one of the allowed values, etc.

That packs a punch.

It’s not even limited in format; you can load from any source. The lib supports JSON, TOML, and YAML out of the box, but you can inherit from PydanticBaseSettingsSource and create your own loader. You can even change the order in which sources are loaded by overloading the settings_customise_sources method on your settings class.

But the cool thing about it is that despite the fact that I have been using this for quite some time, every time I come back to the doc, there is something new.

But it cannot parse sys.argv, can it?

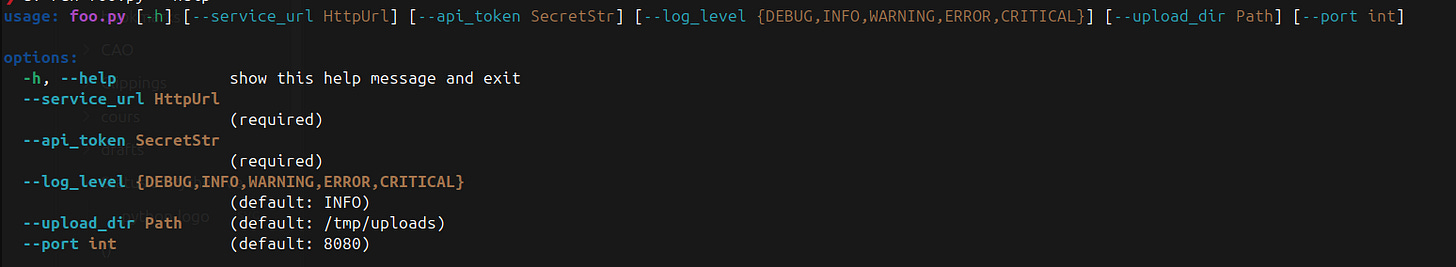

Recently, I learned that, lo and behold, Pydantic settings can now handle command-line arguments. You just need to add one parameter to DictConfig:

model_config = ConfigDict(

env_file=(”/etc/.env”, “.env”),

env_file_encoding=”utf-8”,

cli_parse_args=True

)And boom:

So now you load, convert, and validate cascading settings from 2 dotenv files, env vars, and the CLI. If that’s not beautiful, I don’t know what is:

❯ export API_TOKEN=”yeah_no”

❯ uv run foo.py --service_url https://bitecode.dev --upload_dir /tmp

Service URL: https://bitecode.dev/

API Token: **********

Log Level: WARNING

Upload Directory: /tmp

Port: 8080And the CLI feature comes with many tricks in itself: sub-commands, kebab-case, passing lists/json to set complex values, aliases, --no-flag, positional args, mutually exclusive groups, argparse integration...

It’s a secret

Have you noticed the token is marked as a secret? That’s why if you print it, it will show ***. You need to actively call get_secret_value() to read it, so it doesn’t end up in some log by mistake.

There is a whole part of the lib now that is dedicated to the retrieval of secrets. I can read Unix secret files, docker secrets, AWS secret manager, Google Cloud Secret Manager, and Azure Key Vault, but as you can imagine, you can create your own.

Of course, the community did, so you can also load your token and passwords from a Hashicorp vault

Ironically enough, I was a critic of Pydantic when it came out and preferred to use alternatives. I’m happy to report I’ve done a full 180 on this and use it everywhere.